A view to a kill

until recently, most biologists classified cell deaths into two categories. In apoptosis, genetically programmed suicide shapes an organism or rids it of diseased cells. Necrosis, in contrast, includes cell deaths resulting from some outside force. But the simple classification is being challenged by new revelations. And the new classification emerging could help suggest cures for diseases like cancer.

until recently, most biologists classified cell deaths into two categories. In apoptosis, genetically programmed suicide shapes an organism or rids it of diseased cells. Necrosis, in contrast, includes cell deaths resulting from some outside force. But the simple classification is being challenged by new revelations. And the new classification emerging could help suggest cures for diseases like cancer.

From conception onward, cells divide over and over again. And cell death achieves far more than just crowd control. During fetal development, cell deaths sculpt the body. During sickness, cascades of biochemical events euthanise diseased cells. The typical adult may create 10 billion new cells every day and kill off an equal number. Indeed, cancers stem from cells that do not follow the natural suicide plan that's programmed into an organism's genes. The progeny of these renegade masses of prolific cells eventually set up squatter colonies that crowd out healthy tissues and eat into resources.

Several biologists and pathologists have begun to challenge the simplified classification, calling it misleading. For instance, some researchers have found programmed cell death that bears little resemblance to apoptosis. Others report a novel form of cell homicide that targets malignant cells. They demand a different nomenclature. But more is at stake than just naming names. By misdiagnosing how cells die, some scientists argue, the medical community risks overlooking new ways to halt untimely deaths, or to foster them for the sake of cancer therapy.

Sabina Sperandio, researcher at the Buck Institute for Age Research in Novato, California, usa, stumbled onto evidence for one of these new types of cell death while she was attempting to measure rates of apoptosis in genetically modified human cancer cells. She was able to trigger in the cells a process that didn't look anything like apoptosis.

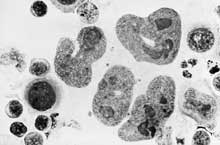

Typically in apoptosis, the membrane of a dying cell softens and blebs balloon out. Meanwhile, the cell's nucleus shrinks and then divides. Eventually, the cells break, which the body's roving cleanup crews discard. Enzymes, called caspases, trigger this apoptosis.

However, in the cells that Sperandio created there was no membrane blebbing, no fragmentation of the nucleus and no cell breakup. Moreover, chemicals that inhibit apoptosis didn't prevent the cells' suicide. Instead, the cells swelled and developed large bubbles, or vacuoles, with liquid inside them. The novel kind of cell suicide was called paraptosis. The Buck Institute scientists are now exploring whether this type of cell death occurs in conditions, such as Huntington's and Lou Gehrig's disease, where some brain damage seems to occur via a mode of cell suicide other than apoptosis. Also, he points out, because malignant cells ignore signals to undergo apoptosis, cancer researchers might enlist paraptosis for new therapies.

Related Content

- Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries

- Standing firm the land and environmental defenders on the frontlines of the climate crisis

- Counting the cost 2022: a year of climate breakdown

- Extreme heat: preparing for the heatwaves of the future

- Decade of defiance: ten years of reporting land and environmental activism worldwide

- Air quality life index: annual update 2022