High and dry

India's prominence in the energy market is that it is the world's sixth largest energy consumer - and yet woefully short of energy sources. It has large coal reserves but the worrisome part is petroleum, which accounts for about 30 per cent of the total energy. India produces only 30 per cent of the 110 million tonnes of petroleum products it consumes. Its share of 0.4 per cent of the world's petroleum reserves is best described as 'traces'. Reserves of natural gas, too, are nothing much to talk about.

India's prominence in the energy market is that it is the world's sixth largest energy consumer - and yet woefully short of energy sources. It has large coal reserves but the worrisome part is petroleum, which accounts for about 30 per cent of the total energy. India produces only 30 per cent of the 110 million tonnes of petroleum products it consumes. Its share of 0.4 per cent of the world's petroleum reserves is best described as 'traces'. Reserves of natural gas, too, are nothing much to talk about.

The 1991 Gulf War showed that energy security in India is a contradiction in terms. Here are some sobering facts.

• Net imports of crude oil and petroleum products more than doubled between 1990 and 1999.

• About 45 per cent of the petroleum consumed in India is imported from the politically volatile Middle East. This is only going to increase.

• If oil prices rise by US $1, India's annual oil bill can increase by US $600 million.

• The International Monetary Fund estimates that every rise of US $5 in the cost of crude oil lowers India's Gross Domestic Product by 0.5 per cent, raises inflation by 1.5 per cent, and leads to an outflow of Rs 18,000 crore.

What India doesn't have is available in plenty in its neighbourhood, be it the gas fields in Bangladesh, Myanmar, the Persian Gulf or the Caspian Sea, or the immense hydroelectric potential of Nepal. Yet the country doesn't seem to be getting any - a reflection on India's diplomatic failures in its backyard.

Subcontinental drift

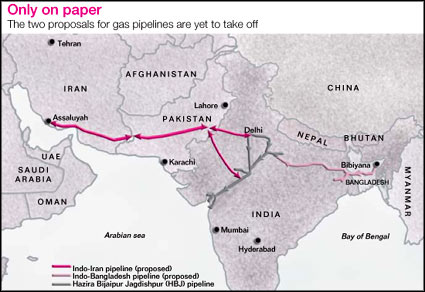

There are two proposals for gas pipelines to India. Unocal of USA, which discovered significant amounts of gas in the Bibiyana field of northwest Bangladesh in 1998, wants to build a 1,363-km pipeline to export 500 million cubic feet (14 million cubic metres) of gas every day for the next 20 years. But the Bangladeshi government has been unable to decide if it wants to allow export of gas to India - the issue is too sensitive politically. Whichever party is in opposition starts whipping up fears of a deal that compromises Bangladesh's interests as Unocal would get the money and India would get the gas (see map: Only on paper) India has now started negotiating with Myanmar for its oil and gas reserves in the hope that Bangladesh will cave in to business demands.

The pipeline from Iran to India via Pakistan has been discussed and debated for over 10 years. But it is getting nowhere due to deteriorating Indo-Pak relations. Pakistan is quite keen on the project - it would earn Pakistan over US $500 million annually as transit fees - but India is not willing. An undersea pipeline fetching gas from Iran or Qatar has gotten nowhere. Another project to fetch gas from Oman has been shelved after eight years of study and expenses of Rs 330 crore. An undersea pipeline is anywhere between two to ten times as expensive as an overland one.

Power games: hydro and nuclear

India is also woefully short of electricity. The prospect of importing electricity from Nepal by building dams has gotten nowhere. There is a lot of talk of expansion of India's nuclear power. A lot of international nuclear power companies have shown interest in India. But any talk of foreign support or investment in nuclear power in India disregards the fact that India is not a signatory to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and is not likely to be any time soon, says G Parthasarthy, former High Commissioner to Pakistan.

India is also working on the fast breeder technology.

In 1997 it began operating the Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research in Kalpakkam. This is primarily due to its precarious position on nuclear fuel: India has vast resources of thorium but limited uranium. "Kalpakkam to my mind is a failure. Fast-breeder technology is dangerous and I don't want my family to live anywhere close to a fast breeder reactor. Thorium is an overrated fuel given the state of technology," says Sunil Dasgupta, journalist and researcher on energy security issues, based at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC.

"Fast-breeder reactors are expensive, largely due to important safety concerns," says M V Ramana, research associate at the programme on science and global security at Princeton University, USA. "Mere availability of an energy resource cannot determine a country's energy strategy. If that were to be the case, then clearly we could derive the required power from solar photovoltaic cells, for example." All said and done, India isn't really trying to free itself from dependence on oil imports.

Related Content

- State of the Climate in Asia 2024

- Order of the National Green Tribunal in the matter of Futala lake pollution, Nagpur, Maharashtra, 05/06/2025

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding pollution of Godavari river, Telangana, 29/05/2025

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding sinking of Liberian ship off the Kochi coast, Kerala, 27/05/2025

- Order of the National Green Tribunal on the demarcation of Nahargarh Wildlife Sanctuary, Jaipur, Rajasthan, 27/05/2025

- Order of the Punjab and Haryana High Court regarding deteriorating medical infrastructure in Punjab, 13/05/2025