Gender bias removed in clinical research

UNDER pressure from women's groups, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) is under orders to ensure that women and minorities are adequately represented in federally-funded clinical research projects. The requirement, imposed by the US Congress on June 10, 1993, would not apply if the NIH director determines such an inclusion poses a health danger or is incompatible with the purpose of the project.

UNDER pressure from women's groups, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) is under orders to ensure that women and minorities are adequately represented in federally-funded clinical research projects. The requirement, imposed by the US Congress on June 10, 1993, would not apply if the NIH director determines such an inclusion poses a health danger or is incompatible with the purpose of the project.

The instruction is a reaction to widespread complaints that clinical research over the years has improperly excluded women for various reasons.

Women's groups in the US, however, contend it is essential to include pregnant women in trials that represent the only source of promising experimental therapy for a life-threatening condition. Medical discrimination against women, these groups allege, is carried out in three ways: So-called women's diseases are less likely to be researched, women are less likely to be included as participants in clinical studies, and women are less likely to be selected as senior investigators.

Validity lost

Researchers at the Institute of Medicine in the US agree all subjects in a clinical trial should be identical, which is why twins are in great demand, but note the gain in scientific validity offered is lost because one can only assume that a drug that works effectively on men works equally well on women.

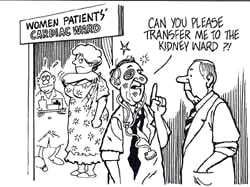

A glaring example of this discrimination is that though 2.5 million US women suffer annually from heart ailments -- and about 500,000 succumb to them making coronary disease the biggest killer of US women -- there is little research information available on cardiovascular illness in women. Worse, there is increasing evidence that treatment of women for cardiac ailments is less frequent than for men, primarily because there is a difference in evaluation of chest pain.

This may explain, according to researchers at medical institutes in the US, why women who undergo coronary bypass surgery are often sicker than men, require emergency surgery more frequently and are referred for surgery at a comparatively later stage. Studies also indicate fewer women than men with coronary disease are referred for exercise rehabilitation, though the functional benefit of such therapy is comparable in men and women.

In keeping with recommendations for cardiovascular research, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced in July, two important steps to ensure new drugs are properly evaluated in women. The first is to emphasise that women must be appropriately represented in clinical research and the second is to stop excluding "women with child-bearing potential" from the earliest phases of clinical trials, altering a policy that was in force for more than 15 years.

Accordingly, drugs must be tested in three phases: The first generally involves small numbers of health volunteers or patients treated over a short period to assess individual tolerance of the drug; the second consists of controlled trials involving a few hundred patients and is intended to establish the drug's effectiveness and relative safety, and the third is the final testing phase before submitting a marketing application.

Interestingly, though FDA's guidelines set down in 1977 clearly state that all age groups should be included in drug testing, they made no requirement for the inclusion of both sexes. In 1988, the FDA amended its guidelines and specifically called for studies to be conducted within population subgroups, defined by characteristics such as sex, age and race.

However, following a review of drug applications submitted between June 1991 and July 1992, which showed only 64 per cent of the safety data had been analysed according to sex, and analysis of the effectiveness data by sex was just 54 per cent, the FDA announced it will hold up new drug applications if sex-specific analyses are not included.