The common root

To appreciate the regenerative potential of sacred groves, we must recognise the whole range of natural, social and spiritual factors that have ensured their survival, relevance and importance. In popular Indian perception and practice, there is no rigid division between the sacred and secular aspects of sacred groves. In Rajasthan, for instance, gochars (common pastures) and oraans (scared woodlots around temples) usually overlap, which is similar to the sacred-secular attitudes towards cows.

Sacred benefits An extensive study of gochars and oraans in western Rajasthan by Shubhu Patwa, a Bikaner-based journalist and activist, has shown that the existence of these pastures and groves is a part of an ancient tradition that incorporated a sense of the sacred with common benefits. This tradition played a vital role in sustaining the pastoral culture and economy in the Thar.

According to a 1937 Bikaner state order, a fine of Rs 25 was levied for grazing sheep in gochars. In 1733, a pasture of 500 ha had been set aside at the request of Nathu Shah, a trader, and named after him as Sada Nathania. Similarly, there are nearly 200 ha of oraan land around the Karnimata temple renowned for its rodents. No tree is allowed to be cut there. When some trees had to be cut to build a railway line through the oraan, the erstwhile ruler of Bikaner paid Rs 100 per tree into the temple account as compensation.

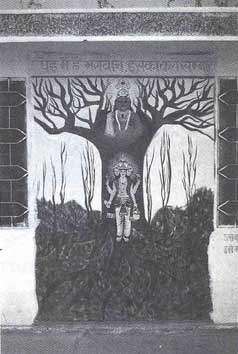

In Udaipur, the sacred grove around Ubeshwar Mahadev, a temple dedicated to Shiva, is surrounded by village pastures. Situated close to a stream, it is also a watering and resting place for cattle. By custom, no cowdung is removed from the area, which is allowed to decay or dry. The dried dung cakes are used to cook bati (local bread) by villagers and pilgrims who visit the temple. The arrangement ensures the sanctity of the domain and provides a plentiful supply of fuel for the benefit of all.

These examples suggest that sacred groves are not only repositories of biotic and genetic diversity but are also the focus of cultural and ethical practices vital for the livelihood of the local community. The Bishnois of Rajasthan and their 29-point ecological ethic for the protection of the khejri tree (Prosopis cineraria) and local wildlife are well known.

Similar codes of social regulation have evolved among other communities. The codes that have been sanctified through association with sacred sites need to be rediscovered. Let me elaborate the sacred in sacred groves through the concept of Vrindavan, the playground of Krishna, Radha and their companions. Here is an inadequate translation of the Hindi poet, Ratnakar"s ode to Vrindavan in spring: "Behold the new Vrindavan, the glorious place of pilgrfiles/images/ The new spring with fresh south breeze, and crimson saplings/ And new buds with new fragrance and young bees greedy for nectar/ The new peacocks and the new nightingales singing new melodies/ The new youth dancing with young maidens, stricken by Cupid with new love and ecstasy beyond consciousness."

While understanding the sacred in sacred groves, it is important to remember that there are aesthetic and religious aspects of these groves that still await discovery. They express themselves in the folklore, songs, rituals and festivals performed around these places. There is also a need to recognise the connections and parallels between the local manifestations and traditions with universal concepts like Vrindavan. There is ample evidence that the larger currents of the Bhakti (devotion) movement and local traditions are informed by the same cultural and ethical roots. And, as the literary and spiritual creativity of Kabir, Nanak, Mira Bai, Amir Khusro and Tagore amply testifies, these sensibilities transcend sectarian boundaries.

This side of wilderness Finally, let us look at sacred groves as commons. According to a commentator, "commons are a cultural space that lie beyond my threshold and this side of wilderness". Custom defines and protects the different uses for each one. The commons are porous. The same spot can be used for different purposes and by different people. And, above all, custom protects the commons. The commons are not a community resource, but become one only when the community encloses them. Enclosure transmogrifies commons into a community resource for the extraction, production or circulation of commodities.

This depiction of commons has even greater validity in the case of sacred groves -- with their multiplicity of purposes, customary protection, lack of enclosure, non-commodity character and their location on "this side of wilderness" -- as an expression of the divine. Sacred groves are, therefore, a refuge for bio-genetic diversity, repositories of ethno-social codes of human relations and regulations vis-a-vis nature, venues of local and universal manifestation of aesthetic traditions and religiosity and cultural spaces between the private domain and the rest of cosmos.

In all these characteristics, sacred groves have undergone a decline under the growth of contemporary natural resource management, dominated by privatisation, energy-intensive technology and commodity markets. Today, all these arrangements are themselves in a state of crisis and face unsustainability. This has led to the search for new patterns of human-nature relationships and the study of scared groves promise rich rewards in this respect.

Kishore Saint works with Ubeshwar Vikas Mandal in Udaipur, Rajasthan.

Related Content

- Engagement of urban local bodies (ULBs) in air pollution control in Delhi: behavioral change; a communication-based approach

- Sub-Saharan Africa: strengthening resilience to safeguard agricultural livelihoods

- How have decentralised natural resource management institutions evolved over 20 years? Summary of findings from Mali, Niger, Sudan and Ethiopia

- Citrate and malonate increase microbial activity and alter microbial community composition in uncontaminated and diesel-contaminated soil microcosms

- Global food security index 2016: an annual measure of the state of global food security

- Adansonia digitata L. (baobab): a review of traditional information and taxonomic description