Waste more want more

DEAD drunk on its political clout, Delhi is blind to the fact that its water scarcity is directly proportional to its gargantuan wastage. At the peak of its "water crisis" in mid-January, Delhi's water consumption, at 215 Ipcd, remained 65 per cent higher than Bombay's.

DEAD drunk on its political clout, Delhi is blind to the fact that its water scarcity is directly proportional to its gargantuan wastage. At the peak of its "water crisis" in mid-January, Delhi's water consumption, at 215 Ipcd, remained 65 per cent higher than Bombay's.

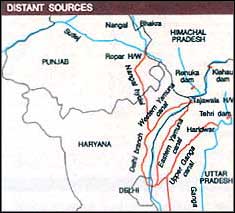

Water supply planners -an oxymoronic term in Delhi's case - have no idea of the water lost in transit from the distant sources. But even conservative estimates put it as high as 900 mld in the dry months. The 220 km- long Narwana branch loses about 225 mld. The loss along the western Yamuna canal till it reaches the Hyderpur treatment plant is put at 190 m.1d. And by the time the water in the Yamuna near Baghpat reaches the Wazirabad treatment plant, it is down to 450 mld - an almost 50 per cent write-off.

And when the Yamuna enters Delhi, its water is almost raw junk. At the entry point at Wazirabad barrage, the water has a colliform count - an indicator of the concentration of pollutants - of 7,500 most probable number (mpn)/100 ml; downstream of Delhi, the colliform count shoots up to an incredible 9 million mpn/100 ml. Gloomier estimates put it at 24 million mpn/100 ml.

The culprit stalks the sewers, the gigantic volume of sewage that the city generates. According to the Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC) records, the 2,300 mld water used in the city generates sewage to the tune of 1,800-2,000 m1d. This is far more than the city's sewage disposal capacity, and the gap between generation and treatment has been growing. In 1956, Delhi generated 216 mld of sewage but could handle 75 per cent of it (see graph). By 1978, the city was ankle-deep in 730 mld of sewage, but the treatment capacity kept pace. However, the system virtually packed up in the burgeoning '80s. By 1985,.only half the 1,360 mld sewage could be treated.

Although official targets for the Eighth Five Year Plan, which has a substantial Rs 282 crore sewage treatment and disposal outlay, aim at augmenting treatment capacities to about 60-62 per cent, cost overruns haunt the projects.

Enhancement might not work anyway. A Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) report warns that "the existing treatment plants do not run to the full designed capacity due to inadequate capacity in the sewerage system". And, even with 18 drains opening into the Yamuna, the expansion of the carrier sewage lines has always lagged behind enhancement and gunk generation.

T Venugopal, CPCB environmental engineer, revealed that a lack of routes has made it "increasingly common for domestic sewer mains to open into storm water drains which lead to the Yamuna". Even according to the conservative DPCC, an untold amount of toxins pour into 1he river riding the 1,200 million litres of untreated sewage.

A 1993 DPCC report also adds that only 31.8 mld of the 2,500 mld of waste water is treated sufficiently for river disposal. "This," says Venugopal, "is meaningless," because this handful of purity mixes with a overwhelming volume of untreated waste water and leaves no trace. The impact of about 20 per cent of waste water given "partial treatment", which entails the removal of insoluble solids, is indeterminate. The CPCB has classified Yamuna in the Delhi stretch as "fit only for irrigation, industrial use and waste water disposal". The latest desperate measure is the appropriately acronymed, Rs 357 crore YAP (Yamuna Action Plan). Unfortunately, only a small component involves Delhi. Of its 900 mld sewage treatment facility, a niggling 20 mld waste water will be from Delhi.

'Its own business'

As Virendra Vats, additional director in the Ganga Project Directorate (which administers YAP), puts it, the disposal of sewage in the national capital "is its own business". But Delhi's earnings from scavenging tax, all of Rs 3 crore, is a matter more for raillery than serious consideration. The operating costs top Rs 40 crore, which works out to Rs 16 for the disposal of 1 kI of sewage. The DWSSDU's accumulated debts tell the story better: at Rs 461.38 crore, they will probably have to be written off.

This virtual bankruptcy is the result of the uneconomical rates at which it provides water to Delhiites. Even frequent and generous over billing, says an MCD survey of selected areas, was of no particular help.

While the MCD estimates that the cost of water is about Rs 2 per kl, it charges as little as 45 paise per kl (upto 20 kl) from domestic consumers who account for as much as 82 per cent of the city's water demand. Commercial consumers are charged at the rate of Rs 3.90 per kl for the first 50 kI. They account for 32.1 per cent of the revenue while consuming 9.3 per cent of the water.

The third category, industrial consumers, are charged a much higher rate - Rs 6.50 per kI upto 50 kl. While they consume just 2.9 per cent of the total water, they contribute up to 21.5 per cent of the revenue.

This is not to say that the MCD doesn't hike its prices:. the last hike, illogically tiny, was just two years ago, but failed to make any impact on the chasm between demand and supply.

Take into account the burden of sewage disposal and the financial management of water in Delhi becomes even more illogical. The entire cost is borne by the state; while effluent load and cost of disposal are growing, nothing has been done to augment the resources of the civic administration. And officials will be the first to admit that the Yamuna has no choice but to continue to be the butt of a metropolis' garbage.

Related Content

- One third of people want more children educated about recycling

- India’s first-ever environmental rating of coal-based power plants finds the sector’s performance to be way below global benchmarks

- Bangladesh State of Environment Report: The Monthly Overview, November, 2014

- Bangladesh State of Environment Report: The Monthly Overview, October, 2014

- An Environmental Agenda for the New Government

- Bangladesh State of Environment Report: The Monthly Overview, March, 2014