Where fishing amounts to thieving

Totladoh is quite an unusual place. For one, work (read fishing) in this Maharashtra village begins only after sunset. Then, the village does not exist legally. Another singularity is its being situated in the heart of the Pench Tiger Reserve, named after the river that passes through it. Just like tigers in the reserve, the village too is threatened by extinction. The forest department wants to do away with it.

Totladoh is quite an unusual place. For one, work (read fishing) in this Maharashtra village begins only after sunset. Then, the village does not exist legally. Another singularity is its being situated in the heart of the Pench Tiger Reserve, named after the river that passes through it. Just like tigers in the reserve, the village too is threatened by extinction. The forest department wants to do away with it.

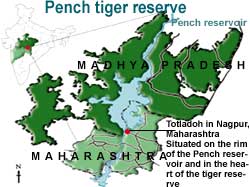

The reserve straddles the Madhya Pradesh-Maharashtra border, covering forested parts of Nagpur, Chhindwara and Seoni districts. A dam is built on the Pench river, which creates a 2,000-hectare reservoir.

The bone of contention is this waterbody over which the people of Totladoh claim their right to fish. But the Supreme Court passed an order, restricting fishing rights in Pench National Park on the Madhya Pradesh side to 305 fisherfolk only. The court did not give any directive for the portion of the reservoir falling in Maharashtra. Consequently, the forest department imposed a ban on fishing, interpreting it as a violation of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972.

More than half of the villagers have cases registered against them in the local courts. Many of them face more than one charge for the same crime: stealing fish, again and again. They attend interminable hearings at the Ramtek division local courts where lies a cupboard packed with files of such cases that have accumulated over the years. "If earning one's livelihood is a crime, we are ready to commit it," says Vinod Gajbiye, the head of Jan Van Andolan Samiti, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) formed by the villagers to demand their rights. "There are two government colonies in the park, the dam itself is not sanctioned by the Union ministry of environment and forests. Why don't they demolish these first," he adds.

Kishore Mishrikotkar, range forest officer, Nagpur, is categorical. "The village is illegal. Its residents are pawns in the hands of the fish mafia of Jabalpur. Fishing is banned in national parks. We have tried to relocate the people, but they refuse to cooperate," he says. "We settled here during the construction of the dam. Later, we learnt to catch fish to eke a living. Where will we go now? Why can't we be allowed to stay in peace?" These are posers put by Worli Devi, a widow settled in Totladoh.

"No scientific evidence suggesting that fishing is harming the ecology of the region has ever been presented," argues Anand Kapoor of NGO Shashwat. He suggests, "If like in Tawa, fishing is regularised and managed by the people, it could perhaps benefit the park." Gajbiye concurs and says, "If we are allowed to handle fishing, we will not need to play hide and seek with the authorities in the forests. This would, in effect, reduce the pressure on the forest."

As Kapoor puts it, "The issues are now more about legalities than rationality. Why can't laws be amended? Why can't people be left to manage their resources?"