BONE BAZAAR

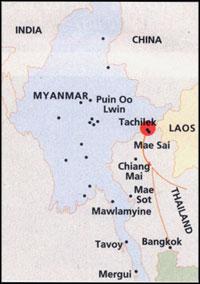

TACHILEK bustles with activity. A busy tourist market, its streets are thronged by buyers, who have travelled many miles to get here. In smuggling circuits, Tachilek is known for selling everything from US-made Marlboros to Chinese fabric. However, buyers flock to this town, not for American cigarettes or cheap Chinese cloth, but for the more exotic merchandise it has to offer. Skins and bones of tigers, leopards, barking deer - Tachilek sells them all, doing brisk trade in body parts of wild animals that, according to international law, are highly endangered. Tachilek, sharing its borders with Thailand and located in the Golden Triangle region notorious for its narcotics trade, has become an one-stop smuggling paradise and a lucrative route for poachers and smugglers in the illegal wildlife trade.

TACHILEK bustles with activity. A busy tourist market, its streets are thronged by buyers, who have travelled many miles to get here. In smuggling circuits, Tachilek is known for selling everything from US-made Marlboros to Chinese fabric. However, buyers flock to this town, not for American cigarettes or cheap Chinese cloth, but for the more exotic merchandise it has to offer. Skins and bones of tigers, leopards, barking deer - Tachilek sells them all, doing brisk trade in body parts of wild animals that, according to international law, are highly endangered. Tachilek, sharing its borders with Thailand and located in the Golden Triangle region notorious for its narcotics trade, has become an one-stop smuggling paradise and a lucrative route for poachers and smugglers in the illegal wildlife trade.

On display are skins of clouded leopards (Neofelis nebulosa), usually thought to be the closest of the living cats to the extinct sabretoothed tiger. Found across the Northeastern Indian range, southern China, Myanmar and Malaysia, this animal has become exceedingly rare and is listed in the Red Data Book on vulnerable Indian animals. Other threatened leopard species such as the Panthera pardus and the leopard cat (Felis bengalensis) are also sold alongside skins of Royal Bengal Tigers, another endangered species. Three subspecies of this animal are already extinct and at the last count, there were only 3,000 to 4,735 of them in the world. All these species are classified under Appendix 1 of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) as "rare or endangered and in which trade is not permitted". But in a blatant violation of this treaty, one can buy a leopard skin here for as little as Thai baht 3,000, roughly Rs 3,000.

Besides skins and bones of large mammals, skulls and horns of Gaur (Bos taxicolor), a species that CITES classifies under Appendix II as "a species that could become threatened if trade is not regulated", and remains of several species of the Asian deer, such as Eld's deer (Cervus eldi), Muntjac, and the Serow are also sold. All these animals are listed under Appendix I.

The bloodied route Though Myanmar signed the CITES treaty last year, custom officials are unaware of trade restrictions on sale of these animal products. In Mae Sai, Thailand, however, officials are better informed. But when asked how the goods could be "taken" across the border, they good-naturedly suggest landing spots down the Mekong river which separates Thailand and Myanmar. And in Tachilek traders assure the buyers that everything can be carried across the border at night, law or no law. Though agencies tracking wildlife smuggling acknowledge that this is a "hot" area, there is very little information about the wildlife black market here. While governments of the Golden Triangle region claim success when it comes to controlling the illicit drug trade, they have failed to stop the animal smugglers. Insurgents in Myanmar are also said to use this trade to acquire money for arms.

Ivory travels through Thailand to Hong Kong and then ultimately to Japan. Skins, bones and other animal parts are usually destined for use as traditional medicines in Thailand. It is thought that the smugglers often take their booty through Thailand back to China. This is because in this warlord Karen-dominated region of Myanmar, transportation through the country is difficult. Thailand provides an easy transit point to other Southeast Asian countries.

Who manages Myanmar's forests?

Myanmar, like India, has enough laws to protect its wild animals. The forest department is responsible for managing and conserving almost 16 per cent of the country's land area. Several laws, such as the 1902 Burma Forest Act and the 1936 Burma Wild Life Protection Act seek establishment of sanctuaries and forest reserves. In 1994, Myanmar passed a new law, Protection of Wild Life and Wild Plants and Conservation of Natural Areas. A committee, under the minister of "natural areas" and zoological gardens, set up conditions for hunting. The forest department also announced a fine of up to 50,000 Kyat (roughly us $400) and/or imprisonment for up to seven years for illegal possession, sale or export of protected species or their body parts. The country even passed a notification of the "completely protected" mammals, birds and reptiles. Of course, this list includes what Tachilek sells openly - tigers and leopards.

But Myanmar is a poor country, with its government and people dependent on natural resources for money. It is also a country that has witnessed recent strife and lawlessness, thanks to ethnic insurgency and military dictatorship. The most important source of foreign exchange, needed for guns and other "essentials", has always been the nation's forest resources. Timber, mostly teak (Tectona grandis), now equals rice as the largest foreign exchange earner. Since 1988, Thai companies have been given contracts to log large areas. Forest cover has dwindled from 42 per cent in 1981 to less than 20 per cent in 1989, making this one the world's five highest deforestation rates. The forest department also exports live animals like elephants, hill mynas and rhesus monkeys. In 1989, the sale of 23 Appendix 1-listed elephants to a Dutch national created an international controversy. Myanmar argued that the elephants had been bred in captivity, a claim that could not be substantiated. In 1990. the CITES secretariat recommended that import licences for elephants from Myanmar should not be granted, unless proved that the animals were really bred in captivity. Elephant sales, however, have continued unabated, and experts believe that their populations have declined drastically.

Like in any other poor country, people of Myanmar are also dependent on wild animals for their survival. The country is well known for its ivory carving. It has the second largest number of elephants in Asia. And though hunting is banned, tusks of elephants that have died naturally can be purchased from the government. Trade in this "government-owned" ivory is legal, and export with certification is allowed.

The most important usage of animal products is in traditional and oriental medicine. Perhaps this is the only health care available to millions in these forested and poverty-stricken regions. Even in Tachilek, modern allopathic drugs are sold alongside traditional Chinese and Burmese concoctions. Traditional Burmese medicine, based on the Ayurvedic system and encompassing some metaphysics of Buddhism, sparingly uses animal products, unlike local Chinese medicines that uses animal parts extensively. Tiger bones are used for strength, python gall bladder for strokes, and wild pig tusk for smallpox. These and many other animal parts are in great demand across the region: the Japanese and the Thais want dried bear gall bladders and tiger bones; South Koreans demand antlers, while the Chinese want everything from pangolin scales and otter skins to swiftlet bird nests and tortoise shells.

Is enforcement possible?

Given this nationwide dependence on wildlife for money, is it possible to enforce laws protecting these endangered animals? The global conservation community has used "stick and guns" to check smuggling. Under CITES, trade bans have been imposed on rogue nations and illicit products are tracked and confiscated. Enforcement is seen as the key to conservation. Despite global action, smuggling and decimation of endangered animals continues. At the ninth meeting of the Conference of Parties to CITES held in 1995, it was accepted that "despite inclusion of tigers in Appendix I, illegal trade has escalated, and could lead to the extinction in the wild". CITES then recommended steps to place tougher sanctions and develop strategies for eliminating the use and consumption of tiger parts and derivatives in traditional medicines, but to little avail. The last meeting of CITES, held in Harare last year, saw the same hysteria about possible extinction of many species. Trade went underground. And the protected tiger, the leopard, the rhino still remain endangered. Clearly, the answer to the crisis in the wild is to be found in action that uses local knowledge and most importantly, sees the animals as resources for poor communities. Otherwise, such markets in Tachilek and many other border towns will flourish. And every smuggling ring that is broken will just be the tip of the iceberg.