Green taxes won`t leave taxpayer in the red

DURING the first 20 years of evolving environmental policy, the name of the game was pollution control. However, this remained very much a game of the North because the South's game was development. The Brundtland Commission came up with an elegant compromise: sustainable development. And, it has proved a challenge for both the South and the North.

DURING the first 20 years of evolving environmental policy, the name of the game was pollution control. However, this remained very much a game of the North because the South's game was development. The Brundtland Commission came up with an elegant compromise: sustainable development. And, it has proved a challenge for both the South and the North.

For the South, sustainable development requires strategies to reduce and eventually halt population increase, strategies to protect biodiversity and the maintenance or development of low-input models of prosperity.

For the North, sustainable development requires massive debt relief -- and not just rescheduling -- and the transfer of pollution control technologies. What is more, the North must arrive at a model of wealth that can be adapted by other countries without destroying the ecological basis of life. This article restricts itself to the North, which faces a formidable challenge.

The inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change has called for a halving of carbon dioxide emissions over the next 40 years, while the World Energy Conference forecasts a doubling of the energy demand over the same period. In all likelihood, this demand will be met largely by fossil fuels, with the nuclear option remaining a limited one because of continuing serious problems. Nevertheless, despite this grim prognosis, there are reasons to be optimistic about the North evolving a model for creating wealth in a sustainable way.

First, technologies and social innovations are available or can be developed to lead to prosperity without depleting non-renewable resources. It should be possible to quadruple energy productivity and thereby raise energy output while lowering carbon dioxide emissions.

Second, there is a misconception that environmental protection is a cost. By using better policy instruments and making certain corrections, environmental protection can be made into an economic benefit and if this is done it will be easy for the poorer countries to join in environmental protection efforts.

Third, the South and the younger generation in the North want done what theory says is possible. The Earth Summit helped greatly to increase this pressure and create a global awareness.

As a new vision of wealth is realised, it will be discovered that the more immediate tasks of debt relief and technology transfer become manageable. So will other pressing environmental issues, such as hazardous waste disposal, acid rain and water pollution. The key is to start making the transition to an economy in which environmental protection equals benefits, rather than costs. Pollution control involves costs without immediate benefits. It works at the end of the pipe, thus adding on costs. Countries or companies evading such costs can usually maintain competitive advantages over those using pollution control technologies. So, pollution prevention pays only if legislation punishes non-complying competitors. But legislation also means costs in terms of administration, surveillance, litigation and training. Small wonder then that less affluent countries show little enthusiasm in adopting -- and enforcing -- high pollution control standards.

In economic terms, the answer to this could be an environment round of GATT, at which rules are negotiated that would allow countries with a high level of environmental protection to introduce import tariffs against "ecological dumping". But, a drawback to this approach is that it restricts free trade.

In addition, there are limits to what protectionism can do for the environment. Most of the damage occurs in countries which cannot afford -- as they see it -- the cost of a strict environmental policy. As long as the focus is on costly pollution control, there seems little hope for the better management of the global environment.

But how can environmental protection be made to benefit both the environment and the economy? The answer is by shifting the emphasis from the end of the pipe to ecologically important, input factors such as energy, water, minerals and land. Improving energy efficiency, for example, would surely benefit the economy. Energy productivity can certainly be tripled. Larger increases are conceivable and switching to environmentally benign energy sources could give further relief. Labour productivity in OECD countries is probably 20 times higher today than it was 150 years ago. In the intervening period, technological progress kept apace with the rise in labour productivity. In contrast, energy productivity increased much more slowly, if at all. In fact, energy consumption rose at about the same rate as economic growth. So much so, that economists even began to believe, with disastrous consequences, that energy consumption is actually an indicator of the wealth of a nation.

Resource efficiency

Today, labour shortage is hardly a problem -- at least not in those sectors of the economy where increased energy consumption substitutes for human muscle power. But energy consumption is a problem and so are water shortages, waste disposal and loss of biodiversity. An improvement in the efficient use of energy, water, minerals or biomass could mean less mining, transport, waste and destruction of the habitat. Higher levels of energy and resource productivity are better indicators of the wealth of a nation than energy consumption.

But what is true at the macro-economic level does not necessarily hold true at the micro-economic level. In fact, resource efficiency is a secondary consideration for most players in the economy, simply because energy, water, minerals and other resources are underpriced. We don't pay anything at all for resource depletion, the greenhouse effect, land degradation or species loss. And, we pay an insufficient price for pollution and waste disposal. Prices at the micro-economic level do not tell the truth because they make it appear that wasting natural wealth is a reasonable activity.

But what is the truth? Lutz Wicke of the German Federal Environment Office, estimated that environmental pollution caused economic damage worth DM 100 billion (Rs 170,000 crore ) for West Germany in 1985, roughly 5 per cent of the country's GNP. In computing this, Wicke restricted himself to classical factors like air, water, soil and noise pollution. If factors like resource depletion and the greenhouse effect were also considered, the figure would more likely be in the range of DM 200 billion (Rs 340,000 crore). Yet, polluters actually pay only about DM 30 billion (Rs 51,000 crore) annually (fig 2). More than half the damage is related to energy production and consumption.

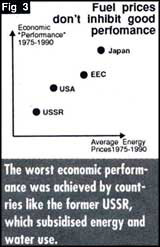

One way of rectifying this situation would be to add between 5 per cent to 10 per cent of a country's GNP to the total price it pays for the use of energy and other resources. Theoretically, this would make countries richer, not poorer, and there is empirical evidence to support this theory. A comparison of the leading industrial powers over the last 15 years shows a direct correlation between high economic performance and high energy prices (fig 3). The worst economic performance was recorded by socialist countries, which heavily subsidised energy and water use. High energy consumption is becoming an indicator of economic backwardness. Emphasising on efficient use of energy and natural resources would make environmental protection a clear benefit. And, pricing is the market tool for promoting this.

Ecological tax reform

Pricing can be influenced either directly via taxes or charges, or indirectly via regulatory constraints or tradeable permits. The latter options tend to involve high administrative and monitoring costs and are therefore unlikely to work effectively in less developed countries. Hence, the choice seems to favour direct pricing of ecologically important input factors. Taxing and controlling unrefined oil, chlorine or mercury is much easier than monitoring effluents or inspecting permits for each transaction.

When it comes to pricing instruments, environment ministers tend to prefer special charges to taxes and to earmark revenue accrued for specific environmental projects. Quantitatively, however, this instrument is limited. Earmarked charges not only place additional financial burdens on the economy, they also require fairly solid evidence of who is the polluter and what remedial measure is justified. Gathering this evidence involves substantial monitoring and control costs and so it is not surprising that the total charges collected in OECD countries is still less than 0.1 per cent of the GDP of those countries.

Unlike charges, environmental taxes are not earmarked and the revenue collected can be used to reduce other taxes. The overall tax burden would thus remain constant even if the state imposed fairly substantial "green taxes", bringing in revenue equal to roughly 5 per cent of GNP, or 50 times the amount of present charges (see fig 4).

Revenue-neutral energy taxes of this size are likely to have an influence far exceeding that of present charges. If we assume that taxes would target fossil and nuclear energy chiefly, the use of renewable energy sources would increase while total energy consumption would shrink. If the price of fossil and nuclear energy doubles, total consumption should drop by some 20 per cent over 15 years. The proportion of energy generated by renewable sources could easily double. Higher price rises would have a still more dramatic impact (fig 5).

If energy and other green taxes are introduced in a revenue-neutral manner, we would have an ecological tax reform rather than the imposition of additional taxes. The reform would encourage human labour, the creation of added value and corporate activities, by substantially lowering the penalties they face currently. It would result in gradually driving wasteful technologies, consumption patterns and infrastructures out of the market (fig 6). To avoid negative distribution effects, some compensation should be offered; in the European context it might be sufficient to lower the Value Added Tax (VAT) which has very similar distributive effects as green taxes. But additional compensation may have to be considered.

Ecological tax reform should proceed slowly but steadily to avoid negative disruptions for producers and consumers. This would allow sufficient time for development in technology, the setting-up of the infrastructure and training and cultural changes. The time frame for such a transition would be in the region of 20 to 50 years.

Some people doubt that there is any price elasticity in the consumption of basic commodities, but they normally think of only short-term elasticity. Long-term elasticity may be observed by examining price levels in different countries over a reasonably long period. Figure 7 shows the per capita petrol consumption of different OECD countries plotted against the petrol price. The negative correlation is striking. For practical reasons, the optimum would be a revenue-neutral tax reform, increasing prices by 5 per cent annually for fossil and nuclear energy, for water and for bulk minerals. In the energy field, many countries begin the process simply by cutting existing tax privileges and subsidies. For problematic substances such as mercury, chlorine, nitrates and the sulphur found in fossil fuels, the price increase could be steeper, without harming the economy. And, to encourage recycling, the tax should apply only to virgin material.

Real benefits

Let us examine the effects such a change might have on different budgets. Energy costs in German industry are estimated to represent some 3.5 per cent of total costs. If energy prices rise by 5 per cent, cost increases would be 0.175 per cent. For private households, the figure would be about 0.25 per cent.

We can further assume macro-economic energy productivity gains of some 3 per cent per year -- a very modest estimate. If energy consumption thus decreases by 3 per cent per year without sacrificing energy services, the annual energy cost differential would be reduced to 2 per cent (5 per cent minus 3 per cent) and the total cost differential for industry would fall to an insignificant 0.07 per cent per year. Moreover, if simultaneous tax reductions worth some 0.2 per cent of total costs are factored in, there would be overall economic benefits for industry as a whole.

For countries like Bangladesh, Egypt or Nicaragua, an increase in energy productivity should provide even more economic benefits than for Germany or Japan. Iran, for instance, would gain far more from a national water pricing policy that radically increases water productivity than would Britain or Canada. Energy productivity gains also help to avoid environmental costs, construction costs for power plants as well as other costs involved in energy production. Thus, they provide multiple benefits.

Obviously, we should not abandon or even freeze command-and-control policies. To cut dioxin releases or chloro-fluoro-carbon (CFC) emissions, a chlorine tax is not even enough. Certain highly toxic substances must be banned altogether. Accident prevention and landscape planning require other legal measures than just pricing.

However, some classical waste and pollution problems will simply disappear when ecological tax reform has worked for some time. Much of the present so-called waste would be turned into valuable materials once energy and raw material prices have risen sufficiently. Dioxin loads could be substantially reduced when chlorine ceases to be cheaply available. Eutrophication of surface water would recede as rising energy prices reduce the influx of nutrients.

Accordingly, after 10 or 20 years of ecological tax reform, it would not be surprising if a new generation of legislators begin cleaning up the thicket of ineffectual environmental regulations that now annoys the corporate world. In particular, they could drop regulations introduced without due consideration in response to local disasters, which have subsequently caused many headaches for company managers.

In place of the current uneven pace of environmental regulation, we would have a long-term, gradual process of tax reform. That sounds too good to be true for the business world and of course, some companies would be on the losing side. But environmental collapse or sudden political panic would produce far more losers.

Ernst Ulrich von Weizsacker is a member of the Club of Rome and the president of the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy. He has co-authored a recent book entitled, Ecological Tax Reform: Policy Proposal for Sustainable Development.