Mekong`s miseries

ENDING over 3 decades of mutual mistrust and hostility on April 5, 1995, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam inked the Mekong River Treaty for "cooperation in the sustainable development of the Mekong River Basin" in Chiang Rai in northern Thailand. Supported by the United Nations Development Programme and after more than 2 years of troubled negotiations, the agreement will bring back decades-old development plans for the lower Mekong river basin.

ENDING over 3 decades of mutual mistrust and hostility on April 5, 1995, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam inked the Mekong River Treaty for "cooperation in the sustainable development of the Mekong River Basin" in Chiang Rai in northern Thailand. Supported by the United Nations Development Programme and after more than 2 years of troubled negotiations, the agreement will bring back decades-old development plans for the lower Mekong river basin.

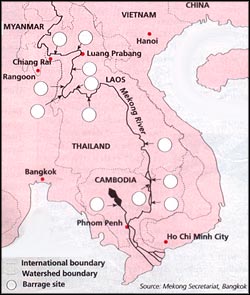

The treaty which defines the scope of cooperation on the Mekong River development for energy, fisheries, navigation, transportation and tourism, also provides for the membership of the upper Mekong countries like China and Burma. The centrepiece of the plans however, is a long string of multi-billion dollar hydroelectric dams to harness the lower Mekong river and its tributaries for industrialization. The Mekong commission will meet formally for the first time in Cambodia in mid-July to discuss this.

Thai and foreign environmental groups have called for the revision of all water development plans since the treaty "appears to be based upon a defunct model of river basin management and plans which have not fundamentally changed over the past four decades". Environmental groups warm that despite the Mekong treaty's call for "sustainable development", the dams could prove a hugely expensive blunder for the biologically diverse Mekong river, forests, wildlife, and millions of local people and ethnic tribes whose homes, farmlands and fishing grounds will be taken away or inundated. Dividing the Mekong waters The text of the Mekong agreement reflects the many compromises reached after 2 years of wrangling among the lower basin countries, especially Thailand and Vietnam. The treaty supersedes the 1957 Statute and the 1975 Declaration on the principles of water use, and sets out the principle of "equitable share and reasonable use" of the common water resource in the lower Mekong basin.

With 6 chapters and 42 articles, the most important feature of the treaty is the change in regulations governing use of the river's water in the dry season by the riparian countries. The treaty denies downstream states the power to veto water diversion from the mainstream and its tributaries, except when carried out in the dry season. While previous rules stressed prior approval by all 4 members states the river water use, the new treaty requires permission from other members of the Mekong Commission only for "inter basin" projects i.e. schemes to divert water from the main body of the river during dry season.

According to Krit Garnjana-goonchorn, director- general, Thai foreign ministry's treaties and legal affairs department, countries that want to use water from the Mekong tributaries in the wet or dry season will have to notify other members.

Despite the signing of the accord and the apparent thaw in regional relations, political distrust runs deep. Downstream Vietnam is worried about the possible impacts on its rice-growing delta. A Vietnames representative, in an interview with Thailand's Nation newspaper said that while Vietnam is satisfied with the restructuring of the Mekong development framework ,"in the Mekong delta, 20 million Vietnamese people rely on agriculture... and seriously depend on the water resources of the Mekong River. So you can imagine the scope of possible impact".

For Thailand, upstream China, which contributes 18 per cent flow for the lower basin, poses significant problems for Thai water diversion schemes. China's plans to build 6 dams on the Mekong mainstream and 9 dams on its tributaries will have potential impacts on Mekong waterflow. Lower basin countries also fear that China can freely dam the Mekong without restricting itself under the Mekong Commission.Along most of its 4,200 kilometer stretch, the Mekong provides fish, irrigates rice fields, and sustains the lives of more than 50 million people-nomadic tribes in southern China, hill-tribe villagers in Burma, farmers and fisherfolk in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam.

The Mekong Secretariat set up by the un in 1957 modified the earlier proposal for "multipurpose" dams for hydropower and irrigation schemes as they had proven uneconomic. It is now proposed to build a cascade of "run-of-river" hydropower projects on the mainstream Mekong. The projects are viewed by the Mekong Secretariat as capable of minimizing the social and environmental impacts to a "practical degree". Run-of-river projects differ from standard high dams in reservoir size as these dams generally store less water.

Eleven potential mainstream dam projects have been culled from 70 overall projects for the Mekong from the Chinese border to the delta in Vietnam. The 11 dams which will have a total capacity of 14,000 mw, will flood 1,900 sq km and displace about 60,000 people. The brunt of impact from the dams will be felt by the Mekong region's local communities with their farmlands and forests flooded, and fisheries disrupted.

Throughout the year, the Mekong caries mud and rocks that are being continually eroded from its beds and banks. This silt, carried and deposited by floodwater to form the extensive, fertile low-lying floodplains and rich fishing grounds of Cambodia and Vietnam provides nutrients for the delta and coastline fisheries.

Fishy fare

The greatest threat from the proposed dams pose is on the region's fisheries representing the main source of subsistence for the local people on the Mekong and its tributaries.

According to Tyson Roberts, an expert with 20 years of research experience on the freshwater fish in Thailand and the Mekong basin, the Mekong river rapids are the centres of biodiversity in rivers akin to coral reefs in the oceans. The river's ecosystem is described as one of the world's richest in fish biodiversity and productivity. In the past 2 years alone, fish biologists have added 3 new species to the list of 1,000 indigeneous species already known, while many more remain to be found. The region's experts warn that the dams will deprive biologists of the last chance to study this complex river system in its relatively undisturbed state. Any reduction in the Mekong's flow could affect the river rapids disrupting the riverine food chain and fish habitat. The dams will block fish migration routes, cutting off spawning and feeding habitat.

Many Mekong species are believed to take annual migrations up and down the largest rivers, including the Mekong mainstream. Schools of Pangasius kempfii, a large economically important catfish reaching more than 1 meter in length and weighing more than 15 kilograms, are believed to travel over 1,000 kilometers from the South China Sea and Mekong Delta in Vietnam up the mainstream past Cambodia and deep into tributaries in Laos and Thailand. Other species, like the huge anguilla eels, known to reproduce far out at sea, and various species of anchovies and herring are also believed to travel up and down the Mekong river from the South China Sea to Laos and Thailand.

After years of conflict and economic isolation, Indochina's governments are eager to commercially exploit the Mekong's resources. The newly-formed Mekong Commission, with the help of the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (adb), is backing corporate investment to raise the capital necessary for Mekong projects.

Noritada Morita, director, adb's Programme Department overseeing the 3 adb-funded hydropower projects in Laos, has hailed the Mekong Commission saying that it was "created for the development of water resources. Regarding this respect, we have to work together to develop the economies of the region".

At the same time, keen to wipe off their losses in developed countries where the dam industry has been virtually stalled by popular protests, dam-building companies are jostling for dam and water-diversion contracts in the Mekong region. The Laos government has already concluded more than 20 agreements for build-own-transfer investments on dams with companies in South Korea, Australia, the United States, Norway, Canada, France, Thailand and Sweden.

As governments proclaim the region's transformation from a battlefield to a marketplace, the rush towards aid, investment and profits appears to ignore the fragility of the Mekong ecosystem and the people who depend on the river for agriculture and fisheries. For the thousands of rural communities soon to be displace, their lands marooned and their fisheries disrupted, the great glittering marketplace promised could almost end up as strenuous battlefields.