Cooperation

bacteria contains genes that give instructions to make proteins, which cause infections. In other words, in the absence of these genes, the bacteria does not harm its host. Called virulence genes, they may code for a protein that helps the bacterium stick firmly to the host. Or it may encode a protein that acts as a toxin to the host or one that helps to inject bacterial products into the host.

bacteria contains genes that give instructions to make proteins, which cause infections. In other words, in the absence of these genes, the bacteria does not harm its host. Called virulence genes, they may code for a protein that helps the bacterium stick firmly to the host. Or it may encode a protein that acts as a toxin to the host or one that helps to inject bacterial products into the host.

Many of these virulence genes are found in clusters known as pathogenecity islands. The answer to how the bacteria acquired these islands during the process of evolution is provided D K R Karaolis, Sita Somara and their colleagues at the University of Maryland, usa (Nature Vol 399, pp 375-379).

The scientists worked with Vibrio cholerae , a bacterium responsible for causing cholera for over a century.Diarrhoea, one of the symptoms of cholera, is said to be caused by a toxic protein that the bacterium releases. However, not long ago, it was discovered that the gene for making the toxin was, in a sense, foreign. The toxin gene was encoded not by V cholerae itself but by a virus (or phage), which is called the cholera toxin phage or ctxF.

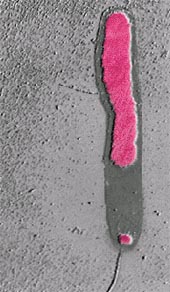

ctxF carries one strand of dna . It manages to get into the bacterium by first sticking to hair-like attachments called pili that extend outward from the bacterium and is used to stick to (colonise) the intestine of its host. The pilus termed toxin co-regulated pilus (tcp) is a fibre of polymerised protein known as t cp a. It promotes colonisation by enhancing interactions between bacterial cells and, perhaps, directly with the host.

tcpa occurs on a pathogenecity island called vpi (for V cholerae pathogenecity island). All strains of V cholerae that cause the disease contain vpi . The astonishing findings that Karaolis and his colleagues have now made is that vpi too is foreign.

It is part of the genetic makeup of a phage, called vpiF . Like ctxF , it too contains a single dna strand surrounded by a coat of protein. The scientists say that, for V cholerae to be capable of causing cholera, it needs to carry two hitchhikers with it. The first, ctxF that endows the bacterium with pili and, the second, vpiF that provides the toxin.

The story does not end there. The coat of protein that surrounds the dna of vpiF is nothing else but t cp a , the very same protein that goes into building the pilus. In other words, the same gene, provides the dna of that phage with a protective protein coat and gives its host bacterium the material to make pili.

While the pilus is necessary for ctxF to infect the bacterium, vpiF provides the means for the other phage to get into V cholerae , a truly extraordinary example of cooperation.

However, whether this relationship is found among other infectious bacteria and how it came to be this way during evolution remain unanswered questions.

Related Content

- Climate risks to nine key commodities: protecting people and prosperity

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding protection of Nahargarh Wildlife Sanctuary, Jaipur, Rajasthan, 18/03/2024

- Human development report 2023/2024

- Effective, inclusive and sustainable multilateral actions to tackle climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution

- Draft disclosure framework on climate-related financial risks, 2024

- Order of the Kerala High Court on human-animal conflict situations, 12/02/2024