Beyond backwardness

ATTEMPTS to industrialise the district of Bidar in Karnataka have backfired because they seem to have brought in more misery in the form of widespread pollution than prosperity to the region. The struggle launched by the locals is targeted at some drug factories in the area that have inundated it with poisonous wastes.

ATTEMPTS to industrialise the district of Bidar in Karnataka have backfired because they seem to have brought in more misery in the form of widespread pollution than prosperity to the region. The struggle launched by the locals is targeted at some drug factories in the area that have inundated it with poisonous wastes.

The history of these factories dates back to the beginning of the '80s when many developed countries began to look for new 'backyards' to dump hazardous wastes. Since the technology to treat toxic substances is more expensive than the manufacture of the drugs themselves many industrialists in developed countries turned to the Third World. Not only did the Indian government welcome these industries but it even offered them a package of lucrative terms which included a five-year tax holiday following installation. Such a policy encouraged a hunt for 'no-industry' districts in the country and Bidar- a declared backward district - was selected as 'one. During 1986-87approximately 110 ha of barren land was acquired from the state forest department for the purpose. In addition, around 678 ha was acquired from the locals for a paltry sum of Rs 1500per ha. Ultimately45large and medium industries were given land to constitute the Kolara industrial area. Several amenities like water, electricity, transport and storage were also provided to them.

Apart from other products the drug factories which :re at the centre of the controversy manufacture base drugs like cyclopropylarnine, norflaxin, hydrochloride and sodium gluconate. Thus the area is known as the 'chemical zone' of Bidar. These units" receive raw materials from abroad and export more than 60 per cent of their products. These drugs then re enter the Indian market wrapped in glossy packing and carrying fancy price tags.

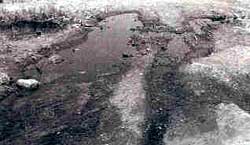

In their enthusiasm to develop Bidar, the official machinery totally ignored the need to regulate the disposal of toxic substances' by these factories. Even as the wastes began pouring in to their backyards the locals had no knowledge of the hazardous nature' of these emissions. The over flowing effluents spread into the nearby fields killing plants and shrubs. Only when the foul-smelling poison started mixing with the waters of the nearby Majara river did the people realise the gravity of the situation. By and by the efflux found its way into the Nizampur tank and the surrounding wells affecting the drinking water supply. Soon the region' s air, water and land were in a state of deterioration. As the health of the locals was exposed to such a serious threat complaints of headache, asthma and diarrhoea increased with most of the victims being children and pregnant women. The residents also harboured a growing suspicion that the poisoned environment was causing sterility. Today women have to walk miles to fetch potable water. Also livestock has depleted by around 30due to the contamination.

For over three years the Karnataka Vimochana Ranga (KVR) hag been organising the villagers against the polluters. Due to the growing concentration of industries in the area and the consequent protests from the people over the discharge of hazardous effluents the government has been compelled to constitute a committee bringing together the District Environment Protection Board the Karnataka Pollution Control Board (KPCB) and the departments of mines and geology, health, agriculture and revenue. The committee came out with a very unfavorable report with respect to the industrialists and stated, "The very purpose of developing industries is being defeated as it is becoming dangerous to human life. It recommended urgent measures and ordered the temporary closure of five polluting factories until remedial measures were undertaken.

But some drug factories like SOL, AgiPI, and Vani, procured a stay order from the Karnataka High Court and continued to pollute the area. Yellappa Reddy the acting chairperson of the KPCB in May1994and Gulam Ahmed chairperson of the body in June1995visited the area and warned the factory owners of dire consequences if they failed to check the harm being caused to the environment. This was followed by the constitution of an expert committee whose report was popularly known as the Kudakavi Report which reiterated the need for a treatment plant. Neither the KPCB nor the government has taken any action to bring this into effect. Such inaction intensified the agitation against the factories.

Meanwhile the factories began employing agents to collect the wastes and dump them on property belonging to consenting land owners at the cost of Rs 50 per tanker. Although the KPCB was forced to refuse the annual clearance to the polluting industries on July 11, 995 the factories have all the same continued to function and spew poisonous wastes due to the stay order. The stay was vacated on September 19,but the KPCB has remained silent. As a last resort - vexed with the complacency of the government - the locals decided to lock up the factories on October 10. The residents of Kolara Hejjarige, Nizampur, Kamalpur and Bellur villages of Bidar district assembled on October 10- under the leadership of the KVR -to press for the closure of the four polluting drug factories located in the Kolara industrial area. Their action invited a violent encounter with the Bidar police over the next few days. Finally on October 16, unable to control the mounting pressure from people from all over the state chairperson of the KPCB, Bengere, was compelled to invoke section 33A of the Water Act and order the shut-down of the four units. The chairperson has also promised that the factories will not reopen until they come out with a time-bound commitment to install a common effluent treatment plant and to sort the pollutants into closed containers. The recommended plant is estimated to cost about Rs six crore of which the Central and the state governments would share 25 percent each. About 40 per cent of the-amount could be borrowed by the industrialists in the form of a soft loan which leaves only 10 per cent of the total costs to be borne by them.

Active lobbying at various levels in the government has resulted in there opening of the factories. And instead of the stipulated area of at least 40 ha only 16 ha is available for the treatment plant. Moreover the area selected for the plant is a religious place Mylara, towards which the locals bear sentiments and which they are therefore unwilling to give up. Agents have also been organising the workers of these factories to start a counter-agitation lest they lose their jobs. To top it all there is also the fear that the factories may procure a stay from the Supreme Court.

But the people of Bidar want nothing less than the closure of the polluting units. Going by the volleying and the counter -volleying it really seems that the battle is far from over.