A bitter prelude to salvation

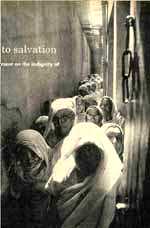

THE WIDOWS of Vrindavan -- heads shaven, white sari-clad, their devotional routine veiling the indignity of penury and starvation -- have long been an emotive subject for photographers the world over. But who are they? What does their plight say for the status of women in rural Bengal -- where most of them come from -- and elsewhere in the country.

THE WIDOWS of Vrindavan -- heads shaven, white sari-clad, their devotional routine veiling the indignity of penury and starvation -- have long been an emotive subject for photographers the world over. But who are they? What does their plight say for the status of women in rural Bengal -- where most of them come from -- and elsewhere in the country.

Foreigners have a perennial fascination for these widows and, not surprisingly, it is Channel Four that has financed the latest documentary on them -- Pankaj Butalia's Moksha. About 80 minutes long, Moksha could have done with much tighter editing. But the statement it makes is devastating: For the love of Lord Krishna, can his richer devotees in the country not ensure a little more food, a little less indignity for these women? It is not a visible indignity, but the invisible one of knowing that you must sing for your supper day in and day out, till you die.

An earlier powerful depiction on the subject was Som and Rita Bakshi's Pukar -- a fictionalised account that ran strikingly close to Butalia's documentary. What lifts Moksha out of the ordinary is the widows' poignant account of themselves. According to one of the women, what upset her most when she first came to Vrindavan was being given khichri on a piece of paper.

Judging from the interviews, ending up in Vrindavan is the final admission of being unwanted -- by children and other relatives. There is a kind of fatality about the statement -- the procession to the dingy, hired rooms in that dirty temple town will not peter out until there are drastic changes in inheritance laws, in social arrangements, in the status of women in the country. Poverty in the countryside embraces all, so why then does it expel only the women, condemning them to a life of no wants, in a faraway, alien milieu?

But Moksha is grim only in its message, not in portrayal. The camera is unwavering, not unsympathetic. It is a sceptical film, not buying the argument that this assembly of widows symbolises willing renunciation, that most of them are at peace in the house of God. Some still hanker for human relationships, for good food, for a home that is not a rented room. Some grieve for marital life, for a husband who died too soon. Others demonstrate a breathtaking economy of existence, such as the disabled woman who sits in a shaded stall, bathing, changing, eating, earning a few coins all at the same spot. "I have neither needs nor wants," she says.

Overlapping voices of the women and snatches from a poem by Butalia form the commentary. Temple scenes are numerous; managers are frequently shown touting these women almost as a tourist attraction. The women sing lyrics of love and marital bliss. The irony is not lost on the viewer. And they will be back in the queue the next day, waiting to collect a pitifully small bag of rice. A bitter prelude indeed to the promised moksha.

But if there isn't much cause for hope, there is still some life, camaraderie and banter that relieves the pathos. That is Butalia's ultimate tribute to this serpentine queue of young and old women, whom nobody wants.