Sleuthing errant genes

Bacteriologists are now taking the help of molecular 'bar codes' made from dna to identify and disable genes that enable bacteria to cause diseases. Once the virulant genes have been identified, researchers can develop antibiotics acting specifically against them and the protein these bacteria make. The new screening system is about 100 times faster than the existing techniques, claims David Holden, who heads the research team at the London-based Royal Postgraduate Medical School. This team is testing the new approach on Salmonella typhimurium -- a bacterium that causes gastroenteritis in humans and a form of typhoid in mice (New Scientist, Vol 147, No 1988).

Bacteriologists are now taking the help of molecular 'bar codes' made from dna to identify and disable genes that enable bacteria to cause diseases. Once the virulant genes have been identified, researchers can develop antibiotics acting specifically against them and the protein these bacteria make. The new screening system is about 100 times faster than the existing techniques, claims David Holden, who heads the research team at the London-based Royal Postgraduate Medical School. This team is testing the new approach on Salmonella typhimurium -- a bacterium that causes gastroenteritis in humans and a form of typhoid in mice (New Scientist, Vol 147, No 1988).

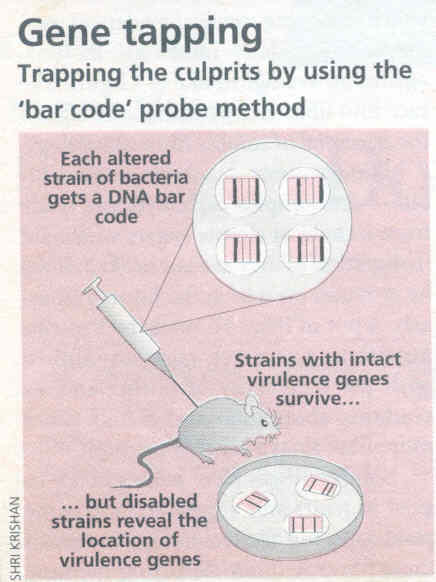

"Virulent genes are the ones that allow bacteria to invade and multiply in their hosts," says Holden. His team has created different strains of S typhimurium by using transposons or 'jumping genes' -- which integrate themselves at random with the bacterial dna, thereby disabling the virulent genes. Each transposon was first labelled with a unique piece of dna -- the molecular 'bar code' -- which researchers can then read with a probe.

The technique essentially works by the process of elimination. Once the mice was infected with the bacteria (the scientists also kept a part of the injected material with themselves for future reference), only virulent strains survived to reach the animal's spleen, where the infection was routinely cleared from blood. The strains that were missing from the animal's spleen were therefore the ones with a disabled virulence gene. Using the bar code probe, the scientists checked the starins found in the spleen against the original material to find which ones were missing: the missing strains were the ones with disabled virulence genes.

Holden's team claims to have screened 1,150 genes out of 4,000 in the bacterial genetic material and have identified 40 disease causing genes. They have also analysed 28 of these in great detail. Of the 28 genes studied, 13 were already known to be virulent genes, indicating that the technique works. Of the remaining 15 genes, 6 exhibited close resemblance to known virulent genes in other bacteria.

The most important advantage of the new technique over conventional methods is that it allows scientists to screen several virulent genes simultaneously. Holden injected each animal with 100 different strains, effectively screening 100 discrete genes in each mouse. Through conventional methods, a researcher had to test each strain in a different animal because there was no way of distingushing one strain from another, says Holden. "We can now do what everyone has been doing before, with 100-fold fewer animals and a hundredth of the time. It is also easy to adapt the technique for use in other types of bacteria and fungi," he says.