The woods are lovely...

COLONIAL forest administration, which didn"t give a damn about the fecund land it was so easily reducing to cinders and stumps, lasted almost a century. The sad thing is that even after Independence, the imperial order of green decimation refused to come unstuck and is now almost pathologically entrenched in the minds of a bureaucracy paralysed by 40 years of self-misrule and a complete lack of a love 0" the land.

COLONIAL forest administration, which didn"t give a damn about the fecund land it was so easily reducing to cinders and stumps, lasted almost a century. The sad thing is that even after Independence, the imperial order of green decimation refused to come unstuck and is now almost pathologically entrenched in the minds of a bureaucracy paralysed by 40 years of self-misrule and a complete lack of a love 0" the land.

This much is starkly evident in the ongoing attempt by the ministry of environment and forests (MEF) to amend the colonial vintage, virtually fungoid, Indian Forest Act of 1927 , which still dictates the rules of governance of Indian forests and people.

Says Madhav Gadgil, ecologist at the Indian Institute of Science, "The onus for the movement is on the foresters to prove whether they are prepared to make the laws of the land relevant to the needs and aspirations of the people they claim to serve, as the Act was framed by the British to scuttle community rights and establish state control over community resources."

The exercise is widely seen as a bum deal: the governmentsponsored Bill ignores mounting historical evidence on the gross, undemocratic inequities of state control over peoples" resources. Pre- and post-Independence peoples" struggles for forest rights have constantly emphasised the need for an alternative management system.

Colonial forest "conservancy" was dictated more by the commercial and strategic utility of certain wood species to feed Britannia"s shipbuilding and the railways which would change the face of international commerce and motility .So the forests were fenced off to regulate community rights. In 1865, the first inspector general (IG).of forests, Sir Dietrich Brandis, established "forest administration" to give officers of the new department sufficient stick to carry out the mandate.

Geriatric government changes There was almost no introspection immediately after -or even decades after -the English left. The first generation of foresters of independent India remained blindly faithful to the imperial diktat to maintain the revenue collecting system through inflexible and coercive state control. C D Pandeya, former inspector general of forests, recalls, "The practising field foresters were told by the government that the importance of their forests division would depend on the amount of revenue It generates.

Soon enough, social pressures built up fit to burst. The government teetered between the fence-and-guard approach to conservation, and the undeniable needs of those people dependent on forests.

The bureaucracy"s views on the present crisis are coloured with an instinct for survival and it ferociously resists any erosion of its authority. It does not view the problem at hand as arising out of administrative ineptitude. M F Ahmed, inspector general, forests, defends himself saying, "Foresters have not failed. It"s true that we have learnt to manage forests through trial and error methods, but pressure on the forests has exceeded manageable limits by far."

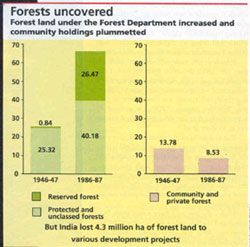

Any crisis -if officially admitted at all -is explained in terms of their shrinking weaponry in the overall administrative setup. "Other departments have infringed upon our decisionmaking powers," says A K Mukherji, former IG, forests.Officials complain petulantly that they couldn"t even resist the decision taken in a higher bureaucratic altitude on the diversion of 4.3 million ha of forest land into commercial ventures before the Forest Conservation Act of 1980 came into force.

They also feel that the abuse of the permits-and-licenses raj by state governments, who have made these their political running capital, has left them helpless and frustrated.

In fact, this has been one of the compelling forces behind the vigorous attempts by the Indian Forest Service to angle for even greater centralisation. The ministry of environment and forests (MEF)"s draft bill seeks to ensure precisely that. "The draft bill will supersede all state laws, vesting the MEF with all powers to decide upon reserving forest land and allowing commercial exploitation of forests. This has already drawn flak from the state governments," says an MEF official.

Supreme Court advocate Rajiv Dhawan views this as an extension of the attempt at extreme centralisation that first found expression in the 42nd Amendment to the Constitution, which brought forests under the Concurrent List, giving the Centre a significant grip on forestry matters. The trend continued with the passing of the Forest Conservation Act of 1980, which gave the Centre powers to decide upon the diversion of forest land for other uses.

Clashes between the conflicting interests of the timber and contractors" lobby, the strong conservation lobby hawking for the protection of wildlife and biodiversity, and the pro-people activists influenced the official attitude. But the subtle transition towards recognising peoples" needs occurred as the unofficial coalition of environment groups gained in strength. Referring to the Committee on Forests and Tribals Report (1982), Roy Burman says, "It had explicitly recognised the symbiotic relationship between forests and the people which, the report admitted, `had suffered a setback"."

The grudging acceptance of participatory management came in the Forest Policy of 1988, which acknowledged that "forests should not be looked upon as a source of revenue," but should be protected for the peoples" wellbeing. It discouraged the commercial exploitation of forests and underscored the importance of community rights over them.

The most significant pressure, however, ballooned up from within the bureaucracy itself. This came due to the hostility which field foresters faced from the local people. The growing, often militant, schism between the State and the people sent the bureaucracy into a tizzy.

Bureaucracy beleaguered

S Palit was an old-school forester in the "70s, given to frequently raiding forests to "recover stolen produce". But on one of his raids in Purulia in June 1973, several officials and local people were injured when the police opened fire to break resistance. Palit, now the chief conservator of West Bengal, confesses, "I became convinced then that there was no alternative to peoples" participation if forests were to survive."

Palit was one among many conscientised converts. Clashes were reported from all over the country, and an Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA) study showed that between 1979 and 1984, at least 51 clashes involving local people and officials were reported from national parks and sanctuaries. A loose, unofficial consensus then evolved: treating communities as hurdles in the protection effort would only negate conservation objectives.

Individual experiments followed during the "70s, mostly in West Bengal, Orissa, Haryana, and Madhya Pradesh. (see box). Unfortunately, due to lack of official support, such informal partnerships withered away when a particular official was relocated. Naturally, conflicts resurfaced. Frustrated with this situation, state forest departments eventually saw in these experiments an opportunity to diffuse tension.

The MEF made a strategic move on June 1, 1990, issuing a circular giving guidelines on Joint Forest Management (JFM). Participatory approach received official sanction, and state governments were urged to take up this model. Even simple economics pushed foresters towards JFM. Considering the budgetary crunch which was choking all their forestry programmes, it made better economic sense to delegate protection responsibilities to the community, saving scarce departmental resources.

Besides, the massive external funding which the forestry sector has been attracting due to the global concern for biodiversity conservation hinges on JFM as an imperative precondition.

However, instead of becoming a blueprint for empowering the people, the JFM model sought to channelise opposition to a more acceptable level. Based on sharing benefits in return for protection, JFM is likely to limit community action within the framework of official planning. The proposed draft bill curbs the scope of participation by making community institutions subservient to the will of the forest department. Communities will perforce execute plans prepared by the department.

The bill further vests state governments with powers to make rules, and they "may prescribe the manner in which the management plan for such forests shall be prepared and executed".

The strongest whip in the hands of the foresters is the concept of "carrying capacity", which is merely a new name for "sustainable extraction", initially mooted by the British to restrict community rights. "It is a red herring which will bring all rights to naught," says Walter Fernandes of the Indian Social Institute.

Interestingly, most officials feel that JFM does not mark a departure from the past. Pandeya insists, "There is a need to acknowledge that certain principles of JFM are not so modern at all." The architects of the current bill have even ignored the progress made in the field within the limited scope of JFM. Ministry officials admit that in their consultations with the states, almost nothing has been said about including the legal provisions made by the different state governments to provide for participatory management.

The JFM experiment shows that the powers granted to forest protection committees (FPCs) are inordinately limited. Chandan Dutta of the Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA) finds this "ridiculous, especially since the government has amended the Constitution to give more powers to local bodies".

Only in Orissa, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Haryana and Andhra Pradesh do FPCs have the right to decide about the distribution of benefits. And only in Bihar and Haryana can they impose fines and punish offenders. Again, Bihar alone allows FPCs to cancel memberships of errant members. In other states, the power lies with the forest department. FPCs are allowed to set rules only in Bihar, Haryana and Andhra Pradesh. Crowning it all is the fact that in most states the forest departments have reserved the right to dissolve FPCs.

Foresters have very carefully avoided issues which might dilute their control. Pune environmentalist Vilasrao Salunke describes it as a "design to make people execute the forest department"s plans, in return for a share of the produce".

Some success stories are even reaching deadlock as beyond a point the community finds its role scuttled. Villagers in Sukhomajri, Haryana, have been successfully nurturing the forests, but are now in a fix, suddenly uncertain about their rights over the valuable khair trees in the forests.

K C Malhotra, an expert on JFM, exposes the systemic flaws. "Even in West Bengal, harvesting rights have not been given to the community. The government retains 75 per cent of the benefits. If the community gets the right to decide about harvesting time, a chunk of the revenue will get locked up."

If this pernickety official attitude persists, numerous community organisations may become completely dependent on the forest departments for their existence. As junior partners, they would have little say over policy and management decisions.

Foresters strongly resent any suggestion about having to doff their powers. As Ahmed puts it, "While foresters will have to open their minds, and not just think `tree", it is also too premature to transfer control to the community."

Community empowerment conjures up in the foresters" minds a vision of chaos and anarchy. They repeatedly cite the case of the northeast, where a very large proportion of forest land is with the district councils and village bodies. S C Dey, additional inspector general of forests, argues, "The dismal state of these forests only proves that community management is a bogey." And S Sunup, chief conservator of Nagaland, echoes, "We have no say in 90 per cent of the state"s forest land. We would like to request the Central government to make the state forest department and the community equal partners under JFM."

Compared to lower level field staff, officials at state and Central levels display greater mistrust of the communities. A Society for the Promotion of Wasteland Development study shows that in West Bengal, lower level forestry staff, including beat officers, showed considerable enthusiasm about participatory methods. They enjoyed their role as spokespersons for community concerns.

Higher officials are uncomfortable dealing with amorphous local opinions. They turn to organised groups, the NGOs, who, as Ahmed sees it, "represent permanence and continuity in a shifting quality of attitudes and interests of local communities." Officials now regard collaborative relationships with established NGOs a key to good public relations.

And having reduced "decentralisation" to such an arrangement, officials feel justified in demanding more authority. They reject outright any proposition for changing the legal status of forest land, quite in conflict with the resource-mapping of the communities themselves. "The revision of ownership patterns of forests (reserve, protected or village forests) will have serious implications. If forests do not have a legal entity, how can you protect them from other uses?" argues Mukherji.

The root of these problems is a warped perspective on forestry. And this stems from the confusion created due to a painfully slow transformation of the curriculum for training forest officials. For long, India suffered from colonisation of the mind, the mantras for which are scripted in the training manuals left behind by the British. Official attitude has been nurtured through these archaic manuals, which are still followed in training forest officials. Commenting on the shortcomings of modern European methods and techniques of forestry, Palit says, "They learnt to apply silvicultural methods that were eminently suitable for simple tree crops. But these were neither based on a sound database, nor pre-tested for Indian field realities."

The curriculum for the Indian Forest Service was restructured only in 1993, to break out of that narrow perspective of mere technical management of forests and plantations. For the first time, a course on `people and forests" was introduced.

But the MEF is still sitting tight on the D P Neog committee report on revision of training courses for state forest service officers, rangers, foresters and forest guards. Neog, former chief conservator of forests, has recommended the need to proselytise about the relationship between tribals and their forests, the contemporary models of development, emerging socio-political implications, and the need and scope of village forests and property rights.

Officials in the MEF also admit that at present there is no permanent faculty in any of the country"s forestry institutions to orient trainees to the sociological aspects of forestry.

The Indian Institute of Forest Management, Bhopal, was established to churn out young forestry graduates, trained in business management, to serve forest-based industries. Ironically, that mandate had to be annulled once the forest policy changed radically in 1988 from commerce and investment-based management to "ecological and social security".

Recent developments have compounded the confusion. The Forest Policy of 1988 talks about involving people, but the amended Wild Life Act (1991) wants them evicted to save wildlife; clandestine efforts are on to push a policy on captive plantation for the industry, although the Forest Policy has categorically maintained that industry should meet its requirements from outside the forests; platitudes to decentralisation are available for a song, and yet all major decisions regarding the use of forest land are being usurped by the Centre. And with a change in global concern for environment management, priorities have become even more complex.

In this scenario, even the NGOs find their struggles getting tougher. Says Fernandes, "A decade ago, when the MEF had tried to introduce a similar forest bill, our fight was simply bipolar -- pro-people vs pro-state. But now, with growing global concern for biodiversity conservation, management objectives are not so simple, after all. There is now a third, pro-conservation lobby to reckon with."

Escape routes

There are apprehensions that the officials might find easy escape routes if the NGOs are divided. And divided they seem to be. As Ashish Kothari of Kalpavriksh points out, "Most urban conservationist groups do not want radical dilution of state control. But those closer to the grassroots movement desire more drastic wresting of controls." A wide body of NGOs involved with the JFM programme are keen on pushing the change through the institution itself and refrain from "forester bashing". With officials now more amenable to peoples" participation, ostensible pragmatists like environmentalist Madhu Sarin say, "I prefer the politics of the feasible to the politics of the desirable."

But for Avdesh Kaushal of the Rural Litigation Entitlement Kendra, who, along with the gujjar villagers of the Rajaji National Park, is fighting against the Wild Life Act"s sweeping powers of evicting people, there is no easy alternative to empowerment. Says he, "Officials must realise that political empowerment can be the only objective for any management strategy."

The outcome of the current debate is awaited. But beyond academic exercises, the powers of officials are constantly being pitted against customary laws. K D Singh, a forester from Arunachal Pradesh, recalls an incident in May 1990 in the Lower Subansiri district. Nishi tribals there had judged 3 forest officers guilty of desecrating their sacred forests and had taken to arms, demanding their immediate suspension, a public apology and payment of fine in valued Mithun calves. The Forest Department bailed out the 3 after they tendered an apology, bowing to the people"s wishes. But will communities ever become powerful enough to bring its errant masters to book?

Chronology of wooden official responses

| Chronology of wooden official responses | |

| 1952 | Increase in supply of industrial timber and maximising revenue earning |

| 1961-66 | 3rd 5 year plan acknowledges the need to meet rural energy requirments |

| 1974-79 | 5th 5 year plan recognises "forest and food, forest and people,and forests and wood" as key links |

| 1976 | National Commission on Agriculture (NCA) looks into the need to revise forest pilicy, continues to focus on checking denudation and meeting industrial needs and held peoples privilages responsible for destruction |

| 1976 | The 42nd amendment to the Constitution makes forestry a Concurrent Subject |

| 1980 | Central government abrogates power to decide about diversion of forest land for non-forest uses. An environmental coalition gains in strength demanding people as the central focus of forest management |

| 1982 | Committees on Forest and Tribals recognises the symbolic relationship between the forests and the people |

| 1988 | Participatory management sanctioned in the Forest-policy |

| 1990 | Guidelines issueed by the ministry of environment and Forest Management |

| 1991 | Wildlife Act amended to make the protection of national parks and sanctuaries more stringent and scuttle all rights by pushing forest dwellers out of the forests |

Deadwood

The Forest Department runs for cover

| 1981-83 | 1989 | 1991 | |

| Dense forest | 10.99 | 11.51 | 11.71 |

| Open forest | 8.41 | 7.83 | 7.60 |

| Mangrove forest | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Scrube area | 2.34 | 2.01 | 1.82 |

| Non-forest(Plantations, etc) | 77.79 | 78.40 | 78.16 |