Pest of a problem

MALARIA, the dreaded killer disease, is staging a comeback with a vengeance. Thought to have been controlled to a large extent if not eradicated altogether, its recurring presence today, has put a formidable question mark on the methods used to eliminate it. The spotlight has returned to the well-known but controversial organochlorine pesticide - dichloro diphenyl trichloro-ethane (DDT) - which has been the mainstay of the malaria eradication pi ogramme initiated by the states apart from malathion and benzene hexachloride (BHC).

MALARIA, the dreaded killer disease, is staging a comeback with a vengeance. Thought to have been controlled to a large extent if not eradicated altogether, its recurring presence today, has put a formidable question mark on the methods used to eliminate it. The spotlight has returned to the well-known but controversial organochlorine pesticide - dichloro diphenyl trichloro-ethane (DDT) - which has been the mainstay of the malaria eradication pi ogramme initiated by the states apart from malathion and benzene hexachloride (BHC).

Although use of certain pesticides are banned, withdrawn or restricted in foreign countries, these very chemicals are being used in India with little thought to their safety Aspects. DDT is one such insecticide whose use has been enmeshed in controversy.

These insecticides have been banned in most of the developed countries, including UK, Australia, USA, Brazil, Denmark, France and Sweden. The reason: it is virtually non-degradable and therefore, highly stressful on the environment. It is known to settle in the far tissues in the human body, and also cause skin rashes and allergies. The after-effects of this compound on the humanbody include tremors, burning or itching sensation, convulsions, joint pains, and liver damage. Further, organo-chlorines are known to leave residues in various living organisms for prolonged periods of their life spin. Besides, it is known to have disrupted reproductive systems of 'non-target' living things found in remote parts of the earth, like penguins in M Antartica to deep ocean fish.

In India, around 1948, DDT - whose properties as in insecticide well discovered in 1939 by Paul Muller - was introduced primarily as a deterrent to crop pests. Other pesticides used for crop protection include malathion, BHC, endosulphan, aldrin and dicifol. DDT made its entry in public health, specifically for the control of malaria Under the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) in 1953, This was later extended towards the total eradication of malaria unclear the National Malaria Eradication Programme (NMEP) in 1958. When subsequent findings on the ill-effects of DDT as a crop pesticide was made public, the Banerjee Committee under the ministry of agriculture, in 1984 recommended its ban in agriculture stating that while it could be used in public health programmes, its consumption should be limited to 10,000 metric tonnes per annum, subject to review. Eventually, the Use of DDT in agriculture was banned from 1989. Another high-level committee which met in 1991, decided to maintain the status quo on the use of DDT in the agricultural sector.

Despite the ban on DDT'S Use, it is still widely being used in controlling Pests like cotton pests in Andhra Pradesh. This has alarmingly led to its entry into the food chain and subsequent deposition in the adipose tissues of humans. Haughtily dismissing this as a matter for concern, A D Pawar, secretary, Central Insecticide Board and National Registration Committee on pesticides, Faridabad, Says "DDT is banned in agriculture and we have washed our hands of it."

But this does not certainly cap the much-debated issue. Malaria is still rampant in many parts of the country. A plethora of reasons can be attributed to its strengthened existence. The tropical climate of India offers an ideal breeding ground for a host of insects, mosquitoes and pests which act as carriers of the parasite protozoa. The problem is compounded with the general lack of hygeine among our people, especially, the poorer class. Anopheles calicifacies proliferates in rural areas. Heaps of uncollected rotting garbage dotting the urban landscape, poor drainage systems in almost every state, water- logged areas which exist even after the monsoon is over add to the misery. The urban thirst for more water storage Lanks, coolers, wells and pumps have furthered the growth of malarial vectors like Anopheles stephensi. Says V P Sharma, director, Malaria Research Centre, New Delhi, "All these factors have caused the malarial cases to increase radically."

There are serious doubts whether in this existing scenario, DDTs usage is justified. "Definitely not,, argues P S Sindbu, professor with the department of chemistry, Delhi University, "Though used for curbing malaria, it has a negative effect on the environment. After it gets into the human food chain, it harms the enzymes in the liver." DDT has also outlived its usefulness as carrier mosquitoes in several regions have become immune to it. Argues Sharma, "Malaria can only be eradicated when there is total people's participation. As for DDT, it is the cheapest and safest insecticide which has saved millions of people front death and all, made development possible."

But the cost factor seems a little too stretched to defend the case of DDT. A T Dudani - formerly with the Voluntary Health Association of India says a strict "no" to the pesticide's use. Staunchly anti DDT, Dudani says that pest control should involve only natural methods. Echoing his view, Sharma opines, "My first choice Would be to practice biological-environemental methods like using fish and bio-larvicides which will reduce the bleeding of vectors, cleaning drams, and chemical-impregnated bednets". But since that these methods have yet to actually take off, he recommends DDT for the time being.

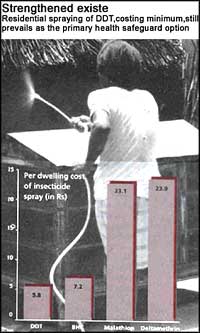

Hindustan Insecticides Limited (UN) - the only public sector organisation manufacturing DDT in the country is all for maintaining the status quo. They still reckon the pesticide to be the safest alternative for curbing malaria vis-a-vis other substitutes,. Says a HIL official when asked to comment on DDTs deleterious effects, "it has only caused the thinning of the egg shells of birds. How does that matter?" However, tile NMEP which is facing flak for its malaria eradication programme going limp, is seeking to use the latest in the market -- synthetic pyrethroids - much to HIL's discomfort. These pyrethroids, already used abroad, are not only potent but also need to be used in smaller doses. Recently, Maharashtra switched to using delta metharine, a synthetic pyrethroid replacing the Conventional DDT. Says S Saluince, director of the public health department in the state, "If DDT needs to be sprayed once every fortnight, delta metharine needs to be sprayed only once every 12 to 14 weeks and has proved to be far more effective than DDT in controlling the mosquito menace."

Officials of HIL who were initially tight-lipped over tile issue, said that the change to synthetic pyrethroids will not last long as cost-wise they are very expensive. These chemicals are four times more costlier than DDT. "How long would the nearly Its 100-150 crore budget to eradicate malaria last if only synthetic pyrethiroids were to be used?, questions P K Joshi, public relations officer of HIL. Added S N Deshmukh, chief, product development, HIL "Resistance development is a phenomenon common to all pesticides and it will not be long before mosquitoes develop resistance to this also." Officials of the Hoechst company who are pushing for tile replacement of DDT with delta metharin, say that the pyrethroid need be used only in small doses unlike DDT, and will still prove to be more effective. Although the cost will be higher, Hoechst officials vouch for the high degree of safety that is attached with delta metharie's application and speak highly of its potency and eco-friendly traits.

Another twist to The whole story lies in the speculation which is rife over DDT's carcinogenic properties. While tests on mice revealed that it could cause tumours, tests on rats which have chromosome patterns more similar to the human physiological system drew a blank. Lack of cogent data on DDT's carcinogenic tendencies shows that it is pushed forward as the only effective insecticide to curb malaria by companies like HIL. At the same time, it is derided by the pro-synthetic pyrethroid lobby consisting mainly of chemical multinational giants like ICI-Zeneca, Hoechst and Bayer.

But K Kanungo, joint director, medical toxicology, Central Insecticides Laboratorv, Fariclabad, says that "as conducting human tests is not possible, taking a chance by Using DDT is not advisable'. He advocates banning the pesticide and adopting synthetic pyrethroids for, unlike DDT, "they are easily bio-degradable and are safer". According to him the main aim behind the application of any pesticide should be to prove toxic and fatal for the carrier insects, but least toxic to human beings. Pyrethroids suit these specifications comfortably.

Meanwhile, the Union ministry of health and family welfare has yet to make Lip its mind over the possible switch to synthetic pyrethroids. Resource crunch is cited as the main reason for delaying the decision. But, saving tile HIL from possible closure should not be a criterion to persist with DDT's usage, when the primary concern should be to safeguard the health of the people.

Related Content

- Order of the National Green Tribunal regarding dumping of waste in open near an educational instituion, Konnagar, Hooghly, West Bengal, 13/11/2024

- Paving the path: a selection of best environmental practices in schools across India

- Paving the path: a selection of best environmental practices in schools across India

- Failed promises: the rise and fall of GM cotton in India

- Transgenic crops: hazards and uncertainties

- Africa’s Got a Tomato Problem: Miner Grubs Are Wiping Them Out