Artificial reefs swell fish catch in Kerala

JUST 5 km north of Kerala's state capital, the 4,000 fisherfolk of Thumba village ready fishing lines and canoes, oblivious of the roar from the Indian Space Research Organisation's launch site nearby. Their catch is mainly kozhuva, hooked along the 7-km natural reef. But with the arrival of fishing trawlers, the catch has become meagre because of overfishing and this has led to frequent disputes between the fisherfolk and the trawler operators.

JUST 5 km north of Kerala's state capital, the 4,000 fisherfolk of Thumba village ready fishing lines and canoes, oblivious of the roar from the Indian Space Research Organisation's launch site nearby. Their catch is mainly kozhuva, hooked along the 7-km natural reef. But with the arrival of fishing trawlers, the catch has become meagre because of overfishing and this has led to frequent disputes between the fisherfolk and the trawler operators.

Conflict between them first broke out in south-west Kerala in 1979, when the fisherfolk, protesting that their catch had declined by 50 per cent because of overfishing, demanded separate fishing zones for themselves and for trawlers.

Over the years, the state government has remained complacent, but voluntary bodies have helped local communities to build artificial coral reefs to raise their fish catch.

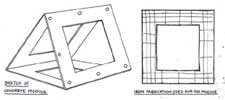

In Thumba, a non-government body called the Programme for Community Organisation (PCO), helped local fisherfolk to build an artificial coral reef by selectively sinking concrete triangular slabs to expand and improve fish and shellfish habitat and thereby increase the fish population. A PCO study showed the artificial coral reef technology could be successfully employed in the Thiruvananthapuram and Kanniyakumari regions. PCO coordinator John Fernandez explained, "We organised the gramakootam (village assembly) and made them aware of the benefits of artificial reef technology."

Persuaded about the viability of the technology, the gramakootam decided to restore the natural reef that had been damaged in December 1990 in the dispute between fisherfolk and trawler owners. It was decided to use concrete triangular slabs and village masons made 30 of them at a cost of Rs 500 each. The slabs, built near the shore for easy transportation, were reinforced with iron rods and boulders. The labour involved in transportation and sinking of the slabs at the reef site, was offered by villagers as shramdaan (voluntary labour) and the total project cost of Rs 15,000 was shared equally between the fisherfolk and PCO.

The rewards were virtually immediate as the fisherfolk reaped a rich fish harvest as early as March 1991. One local fisherman disclosed the kozhuva catch that month was worth Rs 54,000. The reef was immediately declared a community asset and the gramakootam barred fishing at the artificial reef by neighbouring villages. The gramakootam also framed regulations for the users, including a ban on night fishing and setlines and use of big hooks.

Some fisherfolk have expressed dissatisfaction with the concept of equal share for all, arguing that those who put in more effort in building the artificial reef were entitled to a greater share. However, PCO encourages the villagers to overlook minor differences and to settle more serious issues through the gramakootam. One of the major problems last year was maintenance of the artificial reef. Many of the beneficiaries refused to contribute to a maintenance fund, saying that as they paid a tax of 3 per cent of the total catch to the religious authorities, they should be asked to pay for maintenance.