A green front is not enough

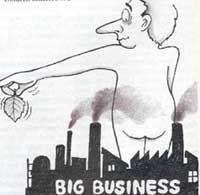

GREEN, the colour now much in fashion, has all kinds of hues. The latest is the green frenzy that has gripped the large corporations. They are scrambling to be seen as environment conscious. Extensive "green ad" campaigns are now a sign of competitiveness. The corporations give and receive awards -- and large ones at that -- for responsible environmental behaviour. Always enamoured with dollar-back green, the tycoons and magnates seem to have finally begun loving other shades of the colour too.

GREEN, the colour now much in fashion, has all kinds of hues. The latest is the green frenzy that has gripped the large corporations. They are scrambling to be seen as environment conscious. Extensive "green ad" campaigns are now a sign of competitiveness. The corporations give and receive awards -- and large ones at that -- for responsible environmental behaviour. Always enamoured with dollar-back green, the tycoons and magnates seem to have finally begun loving other shades of the colour too.

In the prevailing climate of global politics, the greening of the backyards of industry is fashionable politically. Today, governments and the UN are actually asking big business to lead the world in its march towards a greener future.

Why, then, do some of us see red with the prospect of Xerox, Coca-Cola, Dow, 3M, and Turner Broadcasting -- or even Body Shop or Ben & Jerry -- becoming the "environmental conscience" of the world?

The trouble is that environmentalists and green activists have always been hankering for "industry with a green face," but now they feel their own plank has been hijacked.

It may be that I am still uncomfortable with the green hue of industry because I am not sure if this is merely a facelift; or even worse, a mask. Is this a conversion of convenience or a genuine change of faith? Is the new colouring merely epidermal, or has a green heart, and better still, a green soul come to reside within the corporate body?

Given the "yuppiisation" of environmentalism, the corporate world's interest in being seen as green is not surprising. Today, environmental yuppies would rather use twice the amount of recycled paper at twice the unit price, than reduce their waste of paper in the first place; and designer luggage with embroidered cuddly animals sells at 5 times its normal rate.

In such a market, turning green and creating an "environmental niche" may not be the most environmentally kosher thing to do; but not doing so is certainly not good business.

And that is what really irks me. What is being trumpeted and marketed as "green business" is, in fact, no more than "good business". The "success" stories that Stephen Schmidheiny and his friends at the Business Council for Sustainable Development recount in Changing Course, the "sustainable" strategies being touted by Xerox, 3M, and others, and the greening of traditional polluters such as Dow Chemicals, Exxon Oil and their ilk, all seem to be motivated by the gods of cost efficiency and maximised profit.

As an environmentalist, I find nothing wrong with any of this, except on the grounds that the celebration of the greening of corporations may be premature -- and false advertising at that. However, what concerns me much more is the "ungreening" that is destined to come as soon as the easy efficiency gains are exhausted.

In a recession-ridden economy, where a lot of businesses are crippled by waste and inefficiency, a shift towards increasing fuel efficiency and improved waste management is only to be expected. To be truly green, however, corporations would require deep-rooted changes in paradigms and philosophies. There is no sign, even amongst the most (so-called) progressive corporations, that such a shift is forthcoming. What will happen when the honeymoon ends?

The even more fundamental underlying issue here is that of intentions. Should actions only be judged by intentions? Should actions that are good for the environment but motivated by other concerns be celebrated as environmental victories? Is a large corporation which changes over from being energy-profligate to being energy efficient a "greener" entity than a small grassroots outfit that had always been environment conscious? And finally, who is the arbiter of which are good environmental intentions and which are not?

I do not possess answers to any of these questions. I do not know anyone who does. However, that is not reason enough for not raising these uncomfortable questions. In a Hiedeggarian sense, to question is the piety of thought. In an environmental context, the questions that we fail to ask today will haunt our children tomorrow.

---Adil Najam of Pakistan works with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's department of Urban Studies and Planning, and is the Administrator of the International Environmental Negotiation Network at the Programme on Negotiation at Harvard Law School.